Few things have been debated as much as "carbohydrates vs fat."

Some believe that increased fat in the diet is a leading cause of all kinds of health problems, especially heart disease.

This is the position maintained by most mainstream health organizations.

These organizations generally recommend that people restrict dietary fat to less than 30% of total calories (a low-fat diet).

However... in the past 11 years, an increasing number of studies have been challenging the low-fat dietary approach.

Many health professionals now believe that a low-carb diet (higher in fat and protein) is a much better option to treat obesity and other chronic, Western diseases.

In this article, I have analyzed the data from 23 of these studies comparing low-carb and low-fat diets.

All of the studies are randomized controlled trials, the gold standard of science. All are published in respected, peer-reviewed journals.

Most of the studies are being conducted on people with health problems, including overweight/obesity, type II diabetes and metabolic syndrome.

Keep in mind that these are the biggest health problems in the world.

The main outcomes measured are usually weight loss, as well as common risk factors like Total Cholesterol, LDL Cholesterol, HDL Cholesterol, Triglycerides and Blood Sugar levels.

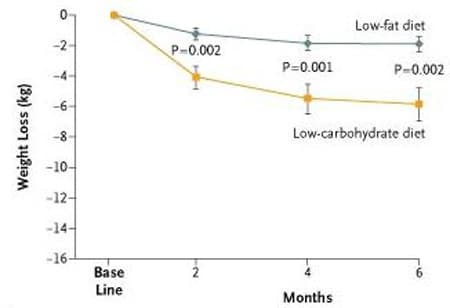

1. Foster GD, et al. A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet for obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 2003.

Details: 63 individuals were randomized to either a low-fat diet group, or a low-carb diet group. The low-fat group was calorie restricted. This study went on for 12 months.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost more weight, 7.3% of total body weight, compared to the low-fat group, which lost 4.5%. The difference was statistically significant at 3 and 6 months, but not 12 months.

Conclusion: There was more weight loss in the low-carb group, significant at 3 and 6 months, but not 12. The low-carb group had greater improvements in blood triglycerides and HDL, but other biomarkers were similar between groups.

2. Samaha FF, et al. A low-carbohydrate as compared with a low-fat diet in severe obesity.New England Journal of Medicine, 2003.

Details: 132 individuals with severe obesity (mean BMI of 43) were randomized to either a low-fat or a low-carb diet. Many of the subjects had metabolic syndrome or type II diabetes. The low-fat dieters were calorie restricted. Study duration was 6 months.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost an average of 5.8 kg (12.8 lbs) while the low-fat group lost only 1.9 kg (4.2 lbs). The difference was statistically significant.

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost significantly more weight (about 3 times as much). There was also a statistically significant difference in several biomarkers:

- Triglycerides went down by 38 mg/dL in the LC group, compared to 7 mg/dL in the LF group.

- Insulin sensitivity improved on LC, got slightly worse on LF.

- Fasting blood glucose levels went down by 26 mg/dL in the LC group, only 5 mg/dL in the LF group.

- Insulin levels went down by 27% in the LC group, but increased slightly in the LF group.

Overall, the low-carb diet had significantly more beneficial effects on weight and key biomarkers in this group of severely obese individuals.

3. Sondike SB, et al. Effects of a low-carbohydrate diet on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factor in overweight adolescents. The Journal of Pediatrics, 2003.

Details: 30 overweight adolescents were randomized to two groups, a low-carb diet group and a low-fat diet group. This study went on for 12 weeks. Neither group was instructed to restrict calories.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 9.9 kg (21.8 lbs), while the low-fat group lost 4.1 kg (9 lbs). The difference was statistically significant.

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost significantly more (2.3 times as much) weight and had significant decreases in Triglycerides and Non-HDL cholesterol. Total and LDL cholesterol decreased in the low-fat group only.

4. Brehm BJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing a very low carbohydrate diet and a calorie-restricted low fat diet on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2003.

Details: 53 healthy but obese females were randomized to either a low-fat diet, or a low-carb diet. Low-fat group was calorie restricted. The study went on for 6 months.

Weight Loss: The women in the low-carb group lost an average og 8.5 kg (18.7 lbs), while the low-fat group lost an average of 3.9 kg (8.6 lbs). The difference was statistically significant at 6 months.

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost more weight (2.2 times as much) and had significant reductions in blood triglycerides. HDL improved slightly in both groups.

5. Aude YW, et al. The national cholesterol education program diet vs a diet lower in carbohydrates and higher in protein and monounsaturated fat. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2004.

Details: 60 overweight individuals were randomized to a low-carb diet high in monounsaturated fat, or a low-fat diet based on the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP).

Both groups were calorie restricted and the study went on for 12 weeks.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost an average of 6.2 kg (13.6 lbs), while the low-fat group lost 3.4 kg (7.5 lbs). The difference was statistically significant.

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost 1.8 times as much weight. There were also several changes in biomarkers that are worth noting:

- Waist-to-hip ratio is a marker for abdominal fat. This marker improved slightly in the LC group, not in the LF group.

- Total cholesterol improved in both groups.

- Triglycerides went down by 42 mg/dL in the LC group, compared to 15.3 mg/dL in the LF group.

- LDL particle size increased by 4.8 nm and percentage of small, dense LDL decreased by 6.1% in the LC group, while there was no significant difference in the LF group.

Overall, the low-carb group lost more weight and had much greater improvements in several important risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

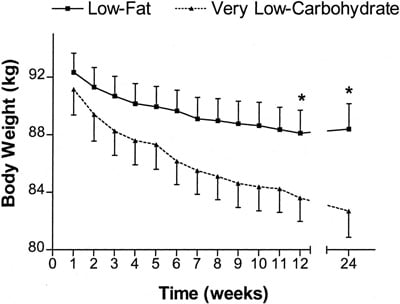

6. Yancy WS Jr, et al. A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-fat diet to treat obesity and hyperlipidemia. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2004.

Details: 120 overweight individuals with elevated blood lipids were randomized to a low-carb or a low-fat diet. The low-fat group was calorie restricted. Study went on for 24 weeks.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 9.4 kg (20.7 lbs) of their total body weight, compared to 4.8 kg (10.6 lbs) in the low-fat group.

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost significantly more weight and had greater improvements in blood triglycerides and HDL cholesterol.

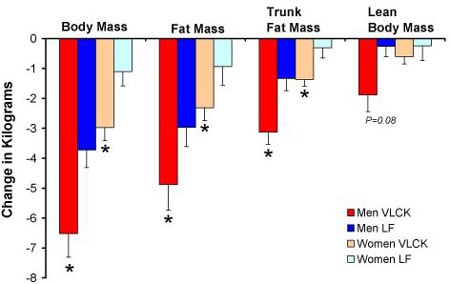

7. JS Volek, et al. Comparison of energy-restricted very low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets on weight loss and body composition in overweight men and women. Nutrition & Metabolism (London), 2004.

Details: A randomized, crossover trial with 28 overweight/obese individuals. Study went on for 30 days (for women) and 50 days (for men) on each diet, that is a very low-carb diet and a low-fat diet. Both diets were calorie restricted.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost significantly more weight, especially the men. This was despite the fact that they ended up eating more calories than the low-fat group.

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost more weight. The men on the low-carb diet lost three times as much abdominal fat as the men on the low-fat diet.

8. Meckling KA, et al. Comparison of a low-fat diet to a low-carbohydrate diet on weight loss, body composition, and risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease in free-living, overweight men and women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2004.

Details: 40 overweight individuals were randomized to a low-carb and a low-fat diet for 10 weeks. The calories were matched between groups.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 7.0 kg (15.4 lbs) and the low-fat group lost 6.8 kg (14.9 lbs). The difference was not statistically significant.

Conclusion: Both groups lost a similar amount of weight.

A few other notable differences in biomarkers:

- Blood pressure decreased in both groups, both systolic and diastolic.

- Total and LDL cholesterol decreased in the LF group only.

- Triglycerides decreased in both groups.

- HDL cholesterol went up in the LC group, but decreased in the LF group.

- Blood sugar went down in both groups, but only the LC group had decreases in insulinlevels, indicating improved insulin sensitivity.

9. Nickols-Richardson SM, et al. Perceived hunger is lower and weight loss is greater in overweight premenopausal women consuming a low-carbohydrate/high-protein vs high-carbohydrate/low-fat diet. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 2005.

Details: 28 overweight premenopausal women consumed either a low-carb or a low-fat diet for 6 weeks. The low-fat group was calorie restricted.

Weight Loss: The women in the low-carb group lost 6.4 kg (14.1 lbs) compared to the low-fat group, which lost 4.2 kg (9.3 lbs). The results were statistically significant.

Conclusion: The low-carb diet caused significantly more weight loss and reduced hunger compared to the low-fat diet.

10. Daly ME, et al. Short-term effects of severe dietary carbohydrate-restriction advice in Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine, 2006.

Details: 102 patients with Type 2 diabetes were randomized to a low-carb or a low-fat diet for 3 months. The low-fat group was instructed to reduce portion sizes.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 3.55 kg (7.8 lbs), while the low-fat group lost only 0.92 kg (2 lbs). The difference was statistically significant.

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost more weight and had greater improvements in the Total cholesterol/HDL ratio. There was no difference in triglycerides, blood pressure or HbA1c (a marker for blood sugar levels) between groups.

11. McClernon FJ, et al. The effects of a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet and a low-fat diet on mood, hunger, and other self-reported symptoms. Obesity (Silver Spring), 2007.

Details: 119 overweight individuals were randomized to a low-carb, ketogenic diet or a calorie restricted low-fat diet for 6 months.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 12.9 kg (28.4 lbs), while the low-fat group lost only 6.7 kg (14.7 lbs).

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost almost twice the weight and experienced less hunger.

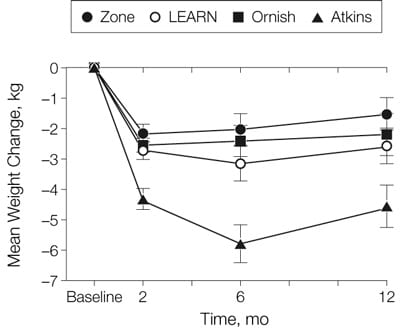

12. Gardner CD, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women: the A TO Z Weight Loss Study. The Journal of The American Medical Association, 2007.

Details: 311 overweight/obese premenopausal women were randomized to 4 diets: A low-carb Atkins diet, a low-fat vegetarian Ornish diet, the Zone diet and the LEARN diet. Zone and LEARN were calorie restricted.

Weight Loss: The Atkins group lost the most weight at 12 months (4.7 kg - 10.3 lbs) compared to Ornish (2.2 kg - 4.9 lbs), Zone (1.6 kg - 3.5 lbs) and LEARN (2.6 kg - 5.7 lbs). However, the difference was not statistically significant at 12 months.

Conclusion: The Atkins group lost the most weight, although the difference was not statistically significant. The Atkins group had the greatest improvements in blood pressure, triglycerides and HDL. LEARN and Ornish (low-fat) had decreases in LDL at 2 months, but then the effects diminished.

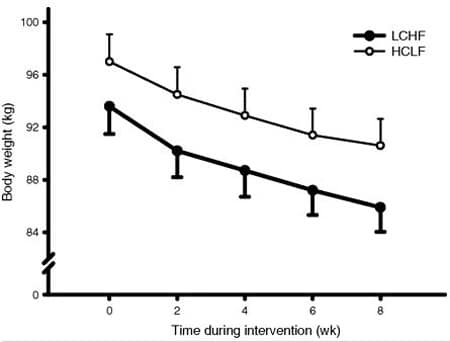

13. Halyburton AK, et al. Low- and high-carbohydrate weight-loss diets have similar effects on mood but not cognitive performance. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2007.

Details: 93 overweight/obese individuals were randomized to either a low-carb, high-fat diet or a low-fat, high-carb diet for 8 weeks. Both groups were calorie restricted.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 7.8 kg (17.2 lbs), while the low-fat group lost 6.4 kg (14.1 lbs). The difference was statistically significant.

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost more weight. Both groups had similar improvements in mood, but speed of processing (a measure of cognitive performance) improved further on the low-fat diet.

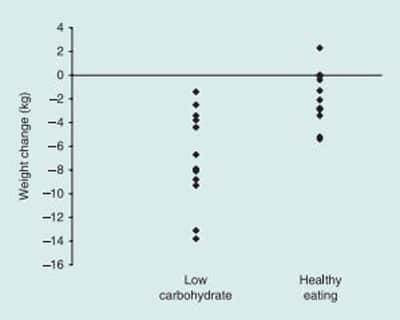

14. Dyson PA, et al. A low-carbohydrate diet is more effective in reducing body weight than healthy eating in both diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Diabetic Medicine, 2007.

Details: 13 diabetic and 13 non-diabetic individuals were randomized to a low-carb diet or a "healthy eating" diet that followed the Diabetes UK recommendations (a calorie restricted, low-fat diet). Study went on for 3 months.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 6.9 kg (15.2 lbs), compared to 2.1 kg (4.6 lbs) in the low-fat group.

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost more weight (about 3 times as much). There was no difference in any other marker between groups.

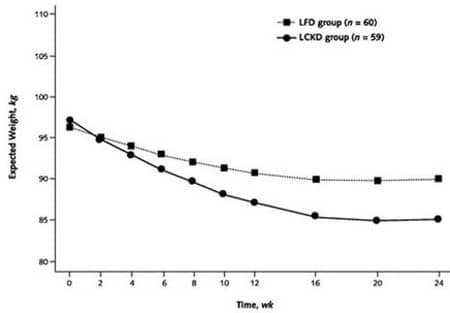

15. Westman EC, et al. The effect of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-glycemic index diet on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutrion & Metabolism (London), 2008.

Details: 84 individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes were randomized to a low-carb, ketogenic diet or a calorie restricted low-glycemic diet. The study went on for 24 weeks.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost more weight (11.1 kg - 24.4 lbs) compared to the low-glycemic group (6.9 kg - 15.2 lbs).

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost significantly more weight than the low-glycemic group. There were several other important differences:

- Hemoglobin A1c went down by 1.5% in the LC group, compared to 0.5% in the low-glycemic group.

- HDL cholesterol increased in the LC group only, by 5.6 mg/dL.

- Diabetes medications were either reduced or eliminated in 95.2% of the LC group, compared to 62% in the low-glycemic group.

- Many other health markers like blood pressure and triglycerides improved in both groups, but the difference between groups was not statistically significant.

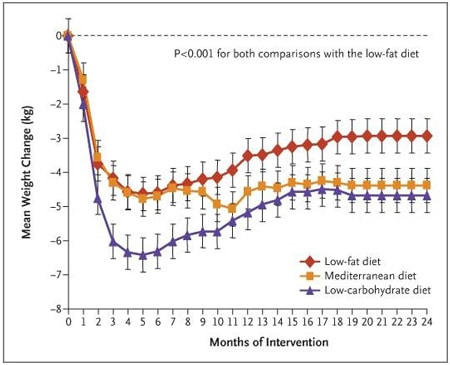

16. Shai I, et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. New England Journal of Medicine, 2008.

Details: 322 obese individuals were randomized to three diets: a low-carb diet, a calorie restricted low-fat diet and a calorie restricted Mediterranean diet. Study went on for 2 years.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 4.7 kg (10.4 lbs), the low-fat group lost 2.9 kg (6.4 lbs) and the Mediterranean diet group lost 4.4 kg (9.7 lbs).

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost more weight than the low-fat group and had greater improvements in HDL cholesterol and triglycerides.

17. Keogh JB, et al. Effects of weight loss from a very-low-carbohydrate diet on endothelial function and markers of cardiovascular disease risk in subjects with abdominal obesity.American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2008.

Details: 107 individuals with abdominal obesity were randomized to a low-carb or a low-fat diet. Both groups were calorie restricted and the study went on for 8 weeks.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 7.9% of body weight, compared to the low-fat group which lost 6.5% of body weight.

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost more weight and there was no difference between groups on Flow Mediated Dilation or any other markers of the function of the endothelium (the lining of blood vessels). There was also no difference in common risk factors between groups.

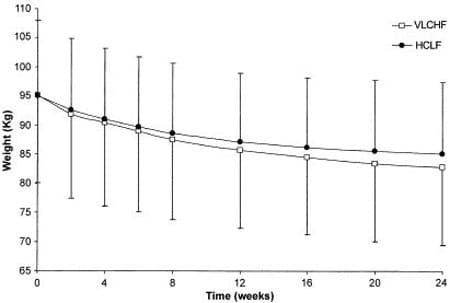

18. Tay J, et al. Metabolic effects of weight loss on a very-low-carbohydrate diet compared with an isocaloric high-carbohydrate diet in abdominally obese subjects. Journal of The American College of Cardiology, 2008.

Details: 88 individuals with abdominal obesity were randomized to a very low-carb or a low-fat diet for 24 weeks. Both diets were calorie restricted.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost an average of 11.9 kg (26.2 lbs), while the low-fat group lost 10.1 kg (22.3 lbs). However, the difference was not statistically significant.

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost more weight. Triglycerides, HDL, C-Reactive Protein, Insulin, Insulin Sensitivity and Blood Pressure improved in both groups. Total and LDL cholesterol improved in the low-fat group only.

19. Volek JS, et al. Carbohydrate restriction has a more favorable impact on the metabolic syndrome than a low fat diet. Lipids, 2009.

Details: 40 subjects with elevated risk factors for cardiovascular disease were randomized to a low-carb or a low-fat diet for 12 weeks. Both groups were calorie restricted.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 10.1 kg (22.3), while the low-fat group lost 5.2 kg (11.5 lbs).

Conclusion: The low-carb group lost almost twice the amount of weight as the low-fat group, despite eating the same amount of calories.

This study is particularly interesting because it matched calories between groups and measured so-called "advanced" lipid markers. Several things are worth noting:

- Triglycerides went down by 107 mg/dL on LC, but 36 mg/dL on the LF diet.

- HDL cholesterol increased by 4 mg/dL on LC, but went down by 1 mg/dL on LF.

- Apolipoprotein B went down by 11 points on LC, but only 2 points on LF.

- LDL size increased on LC, but stayed the same on LF.

- On the LC diet, the LDL particles partly shifted from small to large (good), while they partly shifted from large to small on LF (bad).

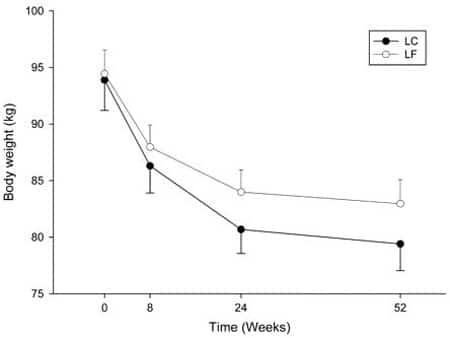

20. Brinkworth GD, et al. Long-term effects of a very-low-carbohydrate weight loss diet compared with an isocaloric low-fat diet after 12 months. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2009.

Details: 118 individuals with abdominal obesity were randomized to a low-carb or a low-fat diet for 1 year. Both diets were calorie restricted.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 14.5 kg (32 lbs), while the low-fat group lost 11.5 kg (25.3 lbs) but the difference was not statistically significant.

Conclusion: The low-carb group had greater decreases in triglycerides and greater increases in both HDL and LDL cholesterol, compared to the low-fat group.

21. Hernandez, et al. Lack of suppression of circulating free fatty acids and hypercholesterolemia during weight loss on a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2010.

Details: 32 obese adults were randomized to a low-carb or a calorie restricted, low-fat diet for 6 weeks.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 6.2 kg (13.7 lbs) while the low-fat group lost 6.0 kg (13.2 lbs). The difference was not statistically significant.

Conclusion: The low-carb group had greater decreases in triglycerides (43.6 mg/dL) than the low-fat group (26.9 mg/dL). Both LDL and HDL decreased in the low-fat group only.

22. Krebs NF, et al. Efficacy and safety of a high protein, low carbohydrate diet for weight loss in severely obese adolescents. Journal of Pediatrics, 2010.

Details: 46 individuals were randomized to a low-carb or a low-fat diet for 36 weeks. Low-fat group was calorie restricted.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost more weight and had greater decreases in BMI than the low-fat group.

Conclusion: The low-carb group had greater reductions in BMI. Various biomarkers improved in both groups, but there was no significant difference between groups.

23. Guldbrand, et al. In type 2 diabetes, randomization to advice to follow a low-carbohydrate diet transiently improves glycaemic control compared with advice to follow a low-fat diet producing a similar weight loss. Diabetologia, 2012.

Details: 61 individuals with type 2 diabetes were randomized to a low-carb or a low-fat diet for 2 years. Both diets were calorie restricted.

Weight Loss: The low-carb group lost 3.1 kg (6.8 lbs), while the low-fat group lost 3.6 kg (7.9 lbs). The difference was not statistically significant.

Conclusion: There was no difference in weight loss or common risk factors between groups. There was significant improvement in glycemic control at 6 months for the low-carb group, but compliance was poor and the effects diminished at 24 months as individuals had increased their carb intake.

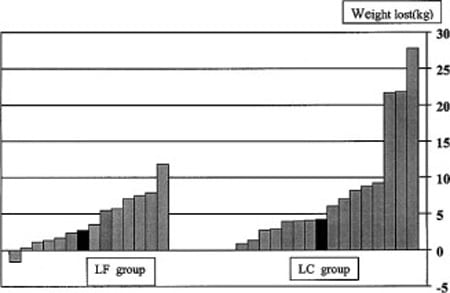

Here is a graph that shows the difference in weight loss between studies. 21 of 23 studies reported weight loss numbers:

The majority of studies achieved statistically significant differences in weight loss (always in favor of low-carb). There are several other factors that are worth noting:

- The low-carb groups often lost 2-3 times as much weight as the low-fat groups. In a few instances there was no significant difference.

- In most cases, calories were restricted in the low-fat groups, while the low-carb groups could eat as much as they wanted.

- When both groups restricted calories, the low-carb dieters still lost more weight (7, 13, 19), although it was not always significant (8, 18, 20).

- There was only one study where the low-fat group lost more weight (23) although the difference was small (0.5 kg - 1.1 lb) and not statistically significant.

- In several of the studies, weight loss was greatest in the beginning. Then people start regaining the weight over time as they abandon the diet.

- When the researchers looked at abdominal fat (the unhealthy visceral fat) directly, low-carb diets had a clear advantage (5, 7, 19).

Two of the main reasons why low-carb diets are so effective for weight loss are the high protein content, as well as the appetite-suppressing effects of the diet. This leads to an automatic reduction in calorie intake.

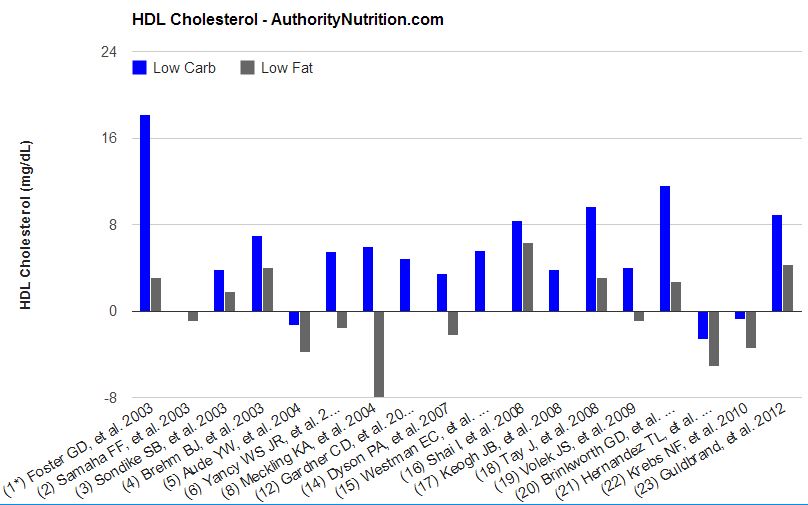

Despite the concerns expressed by many people, low-carb diets generally do not raise Total and LDL cholesterol levels on average.

Low-fat diets do lower Total and LDL cholesterol, but it is usually only temporary. After 6 to 12 months, the difference is not statistically significant.

There have been some anecdotal reports by doctors who treat patients with low-carb diets, that they can lead to increases in LDL cholesterol and some advanced lipid markers for a small percentage of individuals.

However, none of the studies above noted such adverse effects. The few studies that looked at advanced lipid markers (5, 19) only showed improvements.

One of the best ways to raise HDL cholesterol levels is to eat more fat. For this reason, it is not surprising to see that low-carb diets (higher in fat) raise HDL significantly more than low-fat diets.

Having higher HDL levels is correlated with improved metabolic health and a lower risk of cardiovascular disease. Having low HDL levels is one of the key symptoms of the metabolic syndrome.

18 of the 23 studies reported changes in HDL cholesterol levels.

You can see that low-carb diets generally raise HDL levels, while they don't change as much on low-fat diets and in some cases go down.

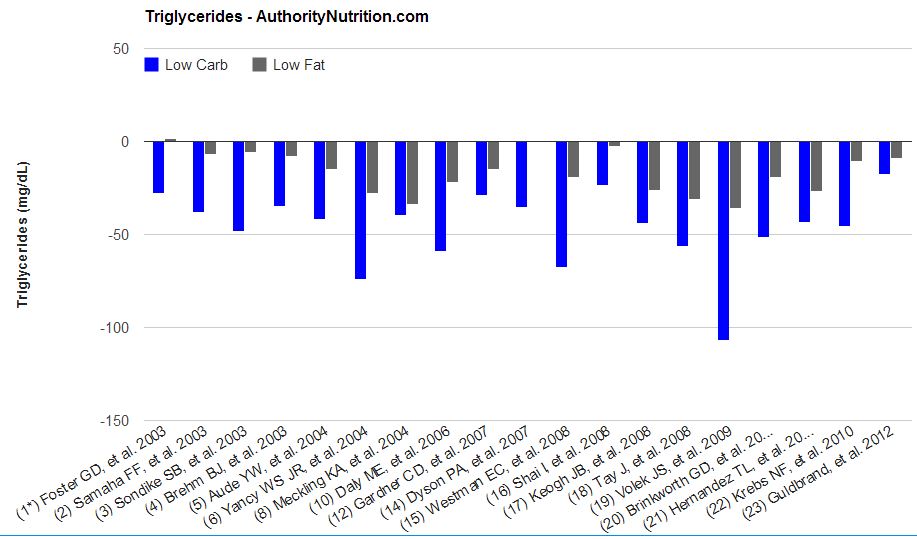

Triglycerides are an important cardiovascular risk factor and another key symptom of the metabolic syndrome.

The best way to reduce triglycerides is to eat less carbohydrates, especially sugar.

19 of 23 studies reported changes in blood triglyceride levels.

It is clear that both low-carb and low-fat diets lead to reductions in triglycerides, but the effect is much stronger in the low-carb groups.

In non-diabetics, blood sugar and insulin levels improved on both low-carb and low-fat diets and the difference between groups was usually small.

3 studies compared low-carb and low-fat diets in Type 2 diabetic patients.

Only one of those studies had good compliance and managed to reduce carbohydrates sufficiently. This lead various improvements and a drastic reduction in HbA1c, a marker for blood sugar levels (15).

In this study, over 90% of the individuals in the low-carb group managed to reduce or eliminate their diabetes medications.

When measured, blood pressure tended to decrease on both low-carb and low-fat diets.

A common problem in weight loss studies is that many people abandon the diet and drop out of the studies before they are completed.

I did an analysis of the percentage of people who made it to the end of the study in each group. 19 of the 23 studies reported this number:

The average percentage of people who made it to the end of the studies were:

Average for the low-carb groups: 79.51%

Average for the low-fat groups: 77.72%

Not a major difference, but it seems clear from these studies that low-carb diets are at the very least NOT harder to stick to than other diets.

The reason may be that low-carb diets appear to reduce hunger (9, 11) and participants are allowed to eat until fullness.

This is an important point, because low-fat diets are usually calorie restricted and require people to weigh their food and count calories.

Individuals also lose more weight, faster, on low-carb. This may improve motivation to continue on the diet.

Despite the concerns expressed by many health experts in the past, there were zero reports of serious adverse effects that were attributable to either diet.

Overall, the low-carb diet was well tolerated and had an outstanding safety profile.

Keep in mind that all of these studies are randomized controlled trials, the gold standard of science. All are published in respected, peer-reviewed medical journals.

These studies are scientific evidence, as good as it gets, that low-carb is much more effective than the low-fat diet that is still being recommended all over the world.

It is time to retire the low-fat fad!

What Are the Key Functions of Carbohydrates?

Biologically speaking, carbohydrates are molecules that contain carbon, hydrogen and oxygen atoms in specific ratios.

But in the nutrition world, they’re one of the most controversial topics.

Some believe eating fewer carbohydrates is the way to optimal health, while others prefer higher-carb diets. Still, others insist moderation is the way to go.

No matter where you fall in this debate, it’s hard to deny that carbohydrates play an important role in the human body. This article highlights their key functions.

One of the primary functions of carbohydrates is to provide your body with energy.

Most of the carbohydrates in the foods you eat are digested and broken down into glucose before entering the bloodstream.

Glucose in the blood is taken up into your body’s cells and used to produce a fuel molecule called adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through a series of complex processes known as cellular respiration. Cells can then use ATP to power a variety of metabolic tasks.

Most cells in the body can produce ATP from several sources, including dietary carbohydrates and fats. But if you are consuming a diet with a mix of these nutrients, most of your body’s cells will prefer to use carbs as their primary energy source (1).

SUMMARY:One of the primary functions of carbohydrates is to provide your body with energy. Your cells convert carbohydrates into the fuel molecule ATP through a process called cellular respiration.

If your body has enough glucose to fulfill its current needs, excess glucose can be stored for later use.

This stored form of glucose is called glycogen and is primarily found in the liver and muscle.

The liver contains approximately 100 grams of glycogen. These stored glucose molecules can be released into the blood to provide energy throughout the body and help maintain normal blood sugar levels between meals.

Unlike liver glycogen, the glycogen in your muscles can only be used by muscle cells. It is vital for use during long periods of high-intensity exercise. Muscle glycogen content varies from person to person, but it’s approximately 500 grams (2).

In circumstances in which you have all of the glucose your body needs and your glycogen stores are full, your body can convert excess carbohydrates into triglyceride molecules and store them as fat.

SUMMARY:Your body can transform extra carbohydrates into stored energy in the form of glycogen. Several hundred grams can be stored in your liver and muscles.

Glycogen storage is just one of several ways your body makes sure it has enough glucose for all of its functions.

When glucose from carbohydrates is lacking, muscle can also be broken down into amino acids and converted into glucose or other compounds to generate energy.

Obviously, this isn’t an ideal scenario, since muscle cells are crucial for body movement. Severe losses of muscle mass have been associated with poor health and a higher risk of death (3).

However, this is one way the body provides adequate energy to the brain, which requires some glucose for energy even during periods of prolonged starvation.

Consuming at least some carbohydrates in the diet is one way to prevent this starvation-related loss of muscle mass. These carbs will reduce muscle breakdown and provide glucose as energy for the brain (4).

Other ways the body can preserve muscle mass without carbohydrates will be discussed later in this article.

SUMMARY:During periods of starvation when carbohydrates aren’t available, the body can convert amino acids from muscle into glucose to provide the brain with energy. Consuming at least some carbs can prevent muscle breakdown in this scenario.

Unlike sugars and starches, dietary fiber is not broken down into glucose.

Instead, this type of carbohydrate passes through the body undigested. It can be categorized into two main types of fiber: soluble and insoluble.

Soluble fiber is found in oats, legumes and the inner part of fruits and some vegetables. While passing through the body, it draws in water and forms a gel-like substance. This increases the bulk of your stool and softens it to help make bowel movements easier.

In a review of four controlled studies, soluble fiber was found to improve stool consistency and increase the frequency of bowel movements in those with constipation. Furthermore, it reduced straining and pain associated with bowel movements (5).

On the other hand, insoluble fiber helps alleviate constipation by adding bulk to your stools and making things move a little quicker through the digestive tract. This type of fiber is found in whole grains and the skins and seeds of fruits and vegetables.

Getting enough insoluble fiber may also protect against digestive tract diseases.

One observational study including over 40,000 men found that a higher intake of insoluble fiber was associated with a 37% lower risk of diverticular disease, a disease in which pouches develop in the intestine as a result of straining during bowel movements (6).

SUMMARY:Fiber is a type of carbohydrate that promotes good digestive health by reducing constipation and lowering the risk of digestive tract diseases.

Certainly, eating excessive amounts of refined carbs is detrimental to your heart and may increase your risk of diabetes.

As soluble fiber passes through the small intestine, it binds to bile acids and prevents them from being reabsorbed. To make more bile acids, the liver uses cholesterol that would otherwise be in the blood.

Controlled studies show that taking 10.2 grams of a soluble fiber supplement called psyllium daily can lower “bad” LDL cholesterol by 7% (10).

Furthermore, a review of 22 observational studies calculated that the risk of heart disease was 9% lower for each additional 7 grams of dietary fiber people consumed per day (11).

Additionally, fiber does not raise blood sugar like other carbohydrates do. In fact, soluble fiber helps delay the absorption of carbs in your digestive tract. This can lead to lower blood sugar levels following meals (12).

A review of 35 studies showed significant reductions in fasting blood sugar when participants took soluble fiber supplements daily. It also lowered their levels of A1c, a molecule that indicates average blood sugar levels over the past three months (13).

Although fiber reduced blood sugar levels in people with prediabetes, it was most powerful in people with type 2 diabetes (13).

SUMMARY:Excess refined carbohydrates can increase the risk of heart disease and diabetes. Fiber is a type of carbohydrate that is associated with reduced “bad” LDL cholesterol levels, a lower risk of heart disease and increased glycemic control.

As you can see, carbohydrates play a role in several important processes. However, your body has alternative ways to carry out many of these tasks without carbs.

Nearly every cell in your body can generate the fuel molecule ATP from fat. In fact, the body’s largest form of stored energy is not glycogen — it’s triglyceride molecules stored in fat tissue.

Most of the time, the brain uses almost exclusively glucose for fuel. However, during times of prolonged starvation or very low-carb diets, the brain shifts its main fuel source from glucose to ketone bodies, also known simply as ketones.

Ketones are molecules formed from the breakdown of fatty acids. Your body creates them when carbs are not available to provide your body with the energy it needs to function.

Ketosis happens when the body produces large amounts of ketones to use for energy. This condition is not necessarily harmful and is much different from the complication of uncontrolled diabetes known as ketoacidosis.

By using glucose instead of ketones, the brain markedly reduces the amount of muscle that needs to be broken down and converted to glucose for energy. This shift is a vital survival method that allows humans to live without food for several weeks.

However, even though ketones are the primary fuel source for the brain during times of starvation, the brain still requires around one-third of its energy to come from glucose via muscle breakdown and other sources within the body (14).

SUMMARY:The body has alternative ways to provide energy and preserve muscle during starvation or very low-carb diets.

Carbohydrates serve several key functions in your body.

They provide you with energy for daily tasks and are the primary fuel source for your brain’s high energy demands.

Fiber is a special type of carb that helps promote good digestive health and may lower your risk of heart disease and diabetes.

In general, carbs perform these functions in most people. However, if you are following a low-carb diet or food is scarce, your body will use alternative methods to produce energy and fuel your brain.

Out Of Topic Show Konversi KodeHide Konversi Kode Show EmoticonHide Emoticon